I’m in London, England. I’ve been here for a week with some friends, attending a Christian conference and taking some time as a tourist. Christendom haunts this city, but it might seem that, mostly, people visit its sights as a kind of relic, tourists jostling to gawk over things that used to be.

The clash here of what many people might refer to as the secular and the sacred is evident all around. In some ways, this place seems very “Christian,” often in the colonial manner in which you might think of nations and powers. My friend hopped in a cab to go to see the Rosetta Stone. He told the cab driver to take him to the British Museum. “I will,” said the cab driver, “but there is nothing British about that museum.” In other words, almost everything there was taken from conquered lands. At the conference we were attending, there was much talk about how there is renewed interest in faith and spirituality in England, particularly among young people. The stats that were shown, with exuberant celebration, were that the percentage of young people attending church had moved from 4% to 12%. Sure, that’s a big increase, but 88 is a lot more than 12.

There are tourists and crowds — big crowds — all over the area in which we are staying. It would be interesting to see from above how unlike a straight line you need to walk as you duck and dive through crowds of quickly walking Londoners navigating through lollygagging, Google-map-gazing tourists. Taking the subway, the Tube, from busy stations is, to me, a wonderful opportunity to observe how swaths of people, going in various directions and finding streams of common current, make up a giant moving, always moving, organism. Tourists like me carry a wary determination to not jump into the wrong human river.

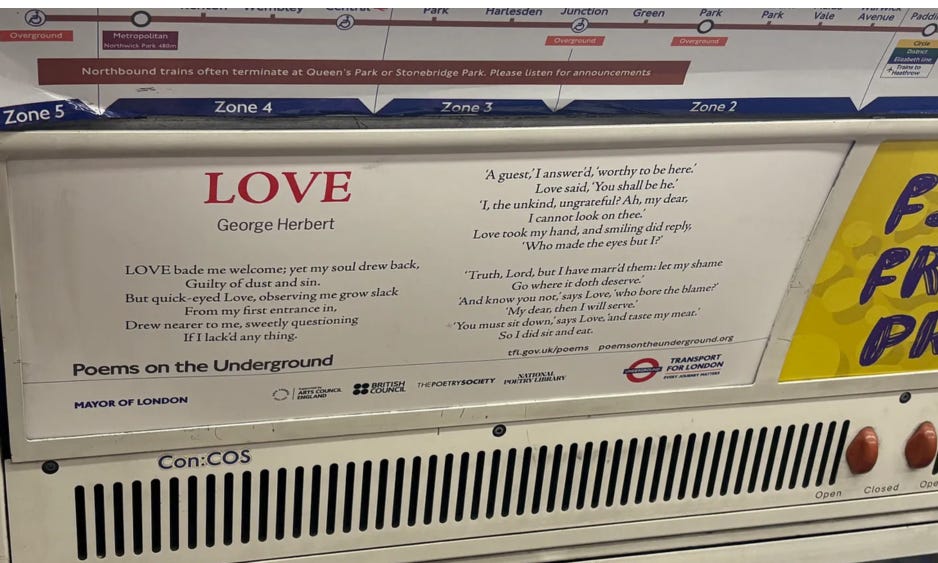

Taking the Tube from Piccadilly or Bakerloo or something like that I hopped on a train to get to a teashop to buy souvenirs for family at home. It was busy. Finding a place to stand without pushing too much into the space of other people is an accomplishment that offers a kind of temporary solace, a rest until the next station. Then, if you choose to not look at your phone, you can look around at the surroundings — the station maps, the advertisements — carefully and unobtrusively noticing other passengers. It was on that trip that, in looking around, I noticed an advertisement. It was offered as a mental health break for those who Sting once said are “packed liked lemmings into shiny metal boxes.” The ad was part of an initiative called “Poetry on the Underground”. I like that name. All poetry these days seems to exist in underground spaces. It so happened that the particular poem was one with which I am familiar. I read it while finishing a theological master’s degree many years ago. The poem is called Love and is by George Herbert. The first time I saw the title it was Love III as Herbert wrote multiple poems with the same name.

Here is the poem;

George Herbert 1593 –1633

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lacked anything.

“A guest,” I answered, “worthy to be here”:

Love said, “You shall be he.”

“I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear,

I cannot look on thee.”

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

“Who made the eyes but I?”

“Truth, Lord; but I have marred them; let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.”

“And know you not,” says Love, “who bore the blame?”

“My dear, then I will serve.”

“You must sit down,” says Love, “and taste my meat.”

So I did sit and eat.

It might not strike you as it did me. I was astounded and moved by it when I read it years ago. It has remained a favourite. It sums up much of what I feel in faith. “Love” in the poem is God or Jesus. The author is invited to a feast which plays as an image of utter peace and welcome. The invited guest feels unworthy and says as much. He offers to serve. The host (Love, God) insists that the guest is made worthy by the host and the invitation. The final image is an acceptance of the invitation.

The poem is very Christian. It’s Christian in a way that I love — an invitation, not a condemnation. The guest is prone to condemn himself, but the host overwhelms such self-judgment with love.

Many Christian voices these days are hollering at the world. As Karl Barth warned decades ago, if the church has only, or even first, a “NO” to the world then the world is right to reject the church. It turns out that 88% in England have done just that, or 96%, either way, just about everybody.

I assume most people walk by the poem without noticing it. There is no interpretation offered on the advertisement. Maybe it’s better that way. A key point of strength in the poem is that the author encountered the love of God in such a way that he accepted the invitation. George Herbert was a priest in the church of England. His writing is said to have influenced William Shakespeare. The poem Love III is not a diatribe against s secularizing world. It is not a warning about the wrath of God. It is, instead, a kind of psalm. A description of being at peace because of the inviting, consoling love of God.

As I finish this reflection I am at Heathrow Airport now. It’s nuts here. I’m assuming that there are no people where you are because they all seem to have wound up in this place, right now. There is little room to move, still less to sit — it’s a contrast to the final image of the poem.

And I pray, on the Tube and in the Terminal; “Dear God, may we know the gracious invitation of your consoling love. And may we speak a faith that is a YES to the world, to every one of these people, to one another, even to me. May we speak invitation, not condemnation.”

I’m here. In London. Everything built is about religion. And yet little is about religion. Or faith. Or love.